Until the Second World War, cardiology and vascular pathology remain a part of the work of the general practitioner.

Technical progress and especially the advent of the means of precise analysis makes it possible to describe and treat cardiovascular diseases encountered overseas.

Later, the creation of an institute of cardiology in Abidjan puts French-speaking Africa on the same level as European countries in the surgical treatment of heart ailments.

THE CARDIOLOGY OF THE GENERAL PRACTITIONER

Until the Second World War, cardiovascular diseases are included in general medicine and can be attended to by the isolated bush doctor or the hospital physician. Besides cosmopolitan diseases, some tropical ailments give rise to cardiac complications. The two most typical items are, on the one hand, beriberi, widespread in Indochina and susceptible of producing sudden death (Le Dantec* in 1929) and, on the other hand, a frequent severe anaemia caused by intestinal parasites (ankylostoma). An attack on the myocardium is also observed in cases of long-lasting malaria, of sleeping sickness and rickettsioses. These latter diseases can also injure the arteries and the veins. Finally, certain anti-parasitic chemotherapies have harmful effects on the heart. F. Blanc* and Bordes* insist on the precautions to be taken when administering emetine prescribed for amoebiasis.

THE PROGRESS OF KNOWLEDGE

Little by little, hospitals are equipped with x-ray apparatuses, then with electrocardiographs. Taken together, the observations of the hospital services permit, especially in Black Africa and in Madagascar, to have an idea of the prevalence of diseases in the hospitals and to give an outline of the epidemiologic details: M. Martin* and Charmot* in Senegal, Mulet* in Guinea, Sankalé* in Sudan, Peuchot* in the Congo, Diénot* in Oubangui, De Lostalot*, Peyrot* and Bertrand* in Madagascar.

Then the progress of Biochemistry, the contribution of Anatomical Pathology and the arrival of the first specialists in Cardiology lead to notable advances in the knowledge of cardiovascular diseases in the tropics. Alas, the patients come very often in an advanced state of the ailment, out of breath and bloated with oedemas. They occupy 10 % of the beds in the medical centres for adults and 20 % of them die in hospital.

A great majority of these African heart patients suffer from cosmopolitan diseases.

– The troubles of infectious origin are due especially to acute rheumatism of the arteries with its dreadful after-effects on the vulva and to venereal syphilis which generates serious aortic lesions.

– High blood pressure, especially in the towns, is as frequent and troublesome as in Europe.

– Of the three heart tunics, the myocardium is most often affected. The concept of "the big primitive heart" of the African, an entity whose origin will be gradually elucidated, is categorized by means of thoracic radiology. Delahousse* and Bertrand* are particularly interested in these unexplained cardiac insufficiencies. In Dakar, in 1960, Sankalé*, with Payet and Pène, draw attention to heart failure in women after childbirth, post-natal myocarditis.

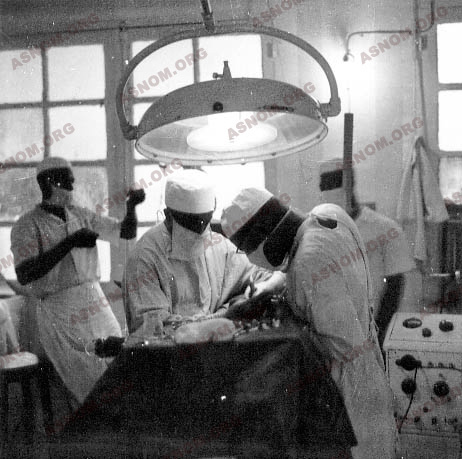

– The first surgical heart operation in the French East African Territories (AOF), performed in 1956, is a commissurotomy for the contraction of a mitral valve, which is crowned with success.

Two facts must be taken into account :

– The relative rarity in Black Africans of coronary thrombosis and obliterating arteritis (endarteritis obliterans) of the lower limbs, two localizations of atheromatosis, frequent in Europe and called "diseases of civilization".

– A group of original heart diseases which seem to have a predilection for tropical regions, such as fibroplastic endocarditis reported by Peuchot* in Brazzaville and the increase in white blood cells (eosinophils) in the heart reported by Mazaud* in Cambodia, endomyocardial fibrosis described by Bertrand* in Abidjan.

THE ABIDJAN INSTITUTE OF CARDIOLOGY

In 1976, profiting from President Houphouet-Boigny’ s learned support, the cardiology institute in Abidjan is inaugurated thanks to Ed. Bertrand*.

It is an autonomous training centre within the university hospital of Treichville. From 1976 to 1988, it is directed by Ed. Bertrand*, a brilliant director of the institute who makes it a modern centre equipped with the most efficient medical and surgical installations with anatomical explorations both non-invasive (echography and mechanography) and invasive (catheterisation and angiography).

The establishment soon becomes famous. Patients arrive from 15 countries, especially to be operated on (instead of being evacuated to Europe or to English-speaking countries). The Institute opens a department of epidemiology of cardiovascular diseases.

Many colonial physicians work in Abidjan together with their Ivorian colleagues and a remarkable heart surgeon, Métras. Notable among them are Clerc* and Renambot*.

The publication of a bilingual review and many works increase the fame of the institute, the breeding ground of numerous African cardiologists. In fifteen years their number rises from 10 to 70. When Bertrand leaves, one of his Ivorian students succeed him.

In the annals of modern cardiology of the Africans, a novel ailment, endomyocardial fibrosis, occupies a preponderant place. It is a curious and fearsome disease where cardiac insufficiency is the consequence of a whitish membrane that develops inside the heart’s cavities. This membrane must be removed in an open-heart operation devised by Dubos, used and adapted by Métras. The Abidjan Institute becomes the authority in this domain and with 120 cases operated on, holds one of the highest records of success in the world.

Finally, there is the price to be paid for excessive smoking, the increase in living standards and the lack of exercise: in the course of forty years, the "diseases of civilization" progress considerably. In the year 2000, myocardial infarction requiring a coronary bypass is no longer rare in the Black African population.

For further information :

– Bertrand Ed. : Précis de pathologie cardio-vasculaire tropicale. 420p. Sandoz Edit. Rueil Malmaison 1979.