Enlarged, red and painful legs, thick and creamy urine, monstrously large limbs or scrotums, fits of asthma... lymphatic filariasis manifests itself in many different forms depending on the individual. These symptoms are due to the obstruction of lower lymphatic vessels by worms of the genus filaria, transmitted to man by the stings of diverse species of mosquitoes.

At the beginning of the 20the Century, the essential elements of the fundamental data concerning the disease are known. The Colonial Health Service determines the geographical distribution of this endemic which, in the zone under French influence, affects dozens of millions of individuals. These physicians participate in the study of the acute manifestations of the disease. The considerable longevity of the worms (more than 15 years) explains the chronic evolution of the ailment with various manifestations, of which the most spectacular is Elephantiasis.

Up to 1947, no medical treatment is efficacious. Only surgery can relieve those who suffer from Elephantiasis. Techniques, which vary in the course of the century, are proposed one after the other and put into practice. In spite of the precarious conditions, success is often remarkable.

The advent of anti-filaria remedies permits the undertaking, notably in Polynesia, of the first chemoprophylaxis mass campaigns.

THE FUNDAMENTAL DATA

In 1862, in Paris, Demarquay discovers embryos of filaria in the blood of a Cuban. The same phenomenon is observed by Wücherer in Brazil in 1866, then in India and Guadeloupe... but it is Bancroft who finds the adult filaria in Australia in 1876. It is named bancroftian filariasis and, later, Wuchereria bancrofti. At the same time, P. Manson designates the mosquito as the transmitting agent of the parasite and Low, in 1900, demonstrates that this transmission is due to the stinging of the insect.

Later, three lymphatic filaria are identified but only Wuchereria bancrofti, a cosmopolitan parasite which only contaminates humans, is to be found in the French colonial domain.

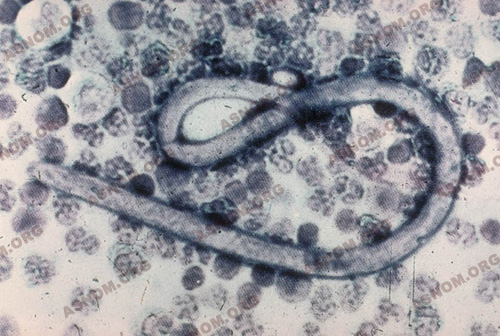

Filaria are thin round worms a few centimetres long. Doted with remarkable longevity, the female, in the course of 15 years, emits millions of larvae (microfilaria). These manifest relatively little aggressiveness and are incapable of evolving into the adult stage in their environment, as passage through mosquitoes is essential for that. At night, they leave the lymphatic vessels to enter the blood stream. At sunrise, as Manson showed in 1877, they are no longer there.

When absorbing their repast, nocturnal mosquitoes imbibe microfilaria together with the blood of a patient.

Adult filaria abide exclusively in the lower lymphatic vessels of the abdomen.

THE GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OF LYMPHATIC FILARIASIS

In Indochina as in the Indian Trading Posts, the physicians of the Colonial Health Service have reported the disease since 1908 in Cochin China (Noc*), in Tonkin (Mathis* and Léger*). The rate of infection is estimated as 15 % in the population of Saigon (Seguin*, Lasnet*, Guérin).

The Pacific Islands are greatly affected (Brochard*). In 1940, 60 % of the population is smitten.

In the West Indies, lymphatic filariasis has been identified since 1907 (Dufougéré*). In 1914, Léger* and Gallen* report the presence of the parasite in 15 % of the population. The situation is the same in Guyana.

In sub-Saharan Africa, Thiroux* in 1912 and Léger in 1913 show the widespread nature of the endemic in the countries of French West Africa (AOF) and French Equatorial Africa (AEF).

In the Indian Ocean, it is the same as in the other territories, notably in Reunion Island (Thiroux*) and the Comoro Islands (Rouffiandis* 1910). There more than 80 % of the population is infected.

The rates of infection are very much superior to the number of patients who show symptoms of filariasis. "Healthy carriers" are numerous and contribute towards the perpetuation of the endemic.

ACUTE MANIFESTATIONS

A few months after contamination, there follow the first acute manifestations. Their repetitive character attracts attention. It is a question of very high fever accompanied by pains in the scrotum and the inguinal region or acute repetitive lymphangitis of the limbs. The leg is swollen and painful, the skin red and glistening. In the groin, the lymph glands are sensitive.

The explanation of these troubles opposes, for a long time, those who favour a microbic origin and those who advocate a filarial origin. The extremely inflammatory aspect leads to the search for a microbic component : besides the streptococcus, some think there is the intervention of a particular germ called the lymphococcus by Dufougéré* and the dermococcus by Le Dantec*. The filaria theory, upheld by Manson, is confirmed by the experience of American military physicians in the Pacific, between 1947 and 1950 : the use of recently-discovered anti-filaria remedies cures their patients afflicted with lymphangitis.

The explanation of the symptoms of filariasis is arrived at thanks to lymphography, x-rays of the opacification of the lymphatic vessels. The obstruction of the vessels by clusters of adult worms, often dead, is responsible for most of the acute manifestations, in particular adenitis and oedemas, which can become more complicated in the case of a microbic superinfection.

The colonial physicians make a great contributions towards the recognition and study of this vascular obstruction, notably in Dakar, Dejou* in 1952, Carayon* in 1962 and Datchary* in 1963. Nowadays, besides the progress in the immunological diagnosis of the disease, non-interventional methods (lymphoscintigraphy and ultrasonography) permit the early detection of lower lymphatic obstructions. When precociously administered, the medical treatment proves to be efficacious.

CHRONIC EVOLUTION - ELEPHANTIASIS

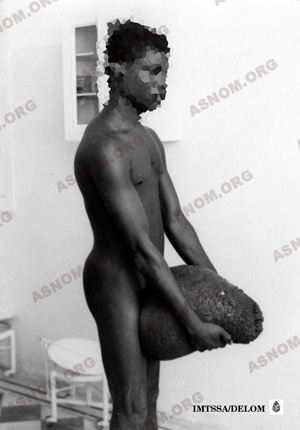

The repeated pressure of acute lymphangitis brings about the fibrous thickening of the skin and the subcutaneous tissue which, at length, can result in monstrous deformations called "Elephantiasis".

The parts of the body in which they usually occur are the legs, the scrotum and sometimes the penis, the vulva, the breasts... The lower limbs can look like the paws of a pachyderm. As for scrotums, becoming huge, they could weigh 30 to 40 kg, so that walking becomes impossible and the use of a wheelbarrow is obligatory for getting about. The penis disappears, embedded in the mass of flesh, but it remains unharmed as are the testicles too. Elephantiasis is here the consequence of a definitive obstruction of the lymphatic vessels, as lymphography confirms.

Lymphatic vessel walls are narrow and fragile and their distension in case of obliteration could end up in their rupture and fistulation. Chyle, abdominal lymph made creamy by fat globules from the digestive tract, then flows in the peritoneum (chyloperitoneum), in the intestine (chylous diarrhoea) or in the urinary tracts (chyluria).

THE TREATMENT OF LYMPHATIC FILARIASIS

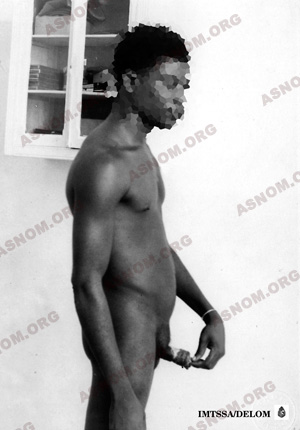

Before the Second World War, no medical treatment yields satisfactory results : iodides, mercurial and arsenical derivatives, anti-streptococcal serum, electro and radiotherapies. Only surgery reduces distressing disabilities of the limbs and the genital organs by ablation of the fibrous mass in order to make the patient once again agile and virile.

Lemoine* is the first to practise "certain palliative interventions" in Tahiti in 1910. He sets about performing vast cutaneous resections called "melon slicing" ("en tranches de melon"). Other techniques are attempted but soon abandoned, such as external draining of the lymph or lympho-venous anastomosis...

In what concerns the scrotum, it is a matter of excising the skin after having extricated the testicles and the penis and then detaching the fibrous mass in one block. A primary obstacle is the volume of these scrotal masses, sometimes huge. The difficulty stimulates the imagination of the surgeons. Some of them suspend this mass from a pulley attached to the ceiling. Guyomarc’h*, about 1910, in French Equatorial Africa (AEF), begins the operation with a large incision in the middle which separates the mass into two symmetric parts. Then he extracts the testicles, the penis... It is the epoch of heroism : the patient is on a stretcher, the operation lasts about thirty minutes. The patient is glad to see his penis once again and to be able to resume sexual activity. Continued by Bernard* in 1911 and by Ouzilleau*, this procedure is used for a long time. The latter writes in 1913: "We have had only four failures in 182 operations". Unfortunately, the recurrence of the ailment is the rule, sooner or later.

After the Second World War, agreement is reached on well-codified techniques to be used in treating elephantiasis of the limbs. Servelle’s techniques or those of Gibson and Touch are used by the surgeons of the Colonial Health Service.

To remedy filarial chyluria, the resection of lymph vessels of the affected kidney, proposed in 1964 by L. Léger, is used with success, particularly in Tahiti, by Fouques*, Huet*, Montangerand* and Roch* in 1967.

MASS ANTI-FILARIA CAMPAIGNS

They only become possible after the discovery of Notezine and they have two aspects :

– The fight against mosquito vectors and their breeding grounds, already undertaken in the combat against Malaria, may explain why today the filarial endemic with its spectacular examples of Elephantiasis is on the decline.

– Chemoprophylaxis, reserved for regions where filarial endemics rage. The whole population may receive Notezine (sometimes incorporated into kitchen salt) during 12 days every three months. Another procedure consists of taking the remedy every two weeks. In 1949, Laigret* begins a campaign in Polynesia and notes, in the population, a great reduction in the density of microfilaria in the blood.

These mass campaigns remain rare and are limited, for, in general, filariasis is not considered a priority. In 1998, the WHO, in a resolution of the General Assembly, demands member states to classify it as a public health problem.

For further information :

– Joyeux Ch. Sice A : Filariose Lymphatique. p. 288. In Précis de Médecine coloniale Masson et Cie Edit. Paris 1937.

– Dejou L. : Les localisations génitales de la filariose de Bancroft en AOF. Med Trop. 1950,10,31-59.

– Carme B. brengues J. Gentilini M. : Filariose lymphatique. Encycl. Méd. Chir. Paris Maladies infectieuses 8-112 A10 3.1980.

– Comité d’experts de l’OMS : Filariose lymphatique. OMS. Séries de rapports techniques. n° 702. 1984.

– OMS : La lutte contre la filariose lymphatique. Genève 1988.